Dominion Atlantic Railway Digital Preservation Initiative - Wiki

Use of this site is subject to our Terms & Conditions.

NRHS Bulletin 1st Quarter 1962 - Land Of Evangeline

NRHS Bulletin 1st Quarter 1962 - Land Of Evangeline

Note: transcribed text of this article is shown below the article photographs, for ease of reading and for search purposes.

IN THE LAND OF EVANGELINE

by Robert Albury

(EDITOR’S NOTE: The following article was written a year or so ago, and some of the statements may not be current. As an example, both the major Canadian roads have vastly expanded their piggyback services since the writing. But the Dominion Atlantic’s charm remains, and past history listed herein is of interest).

As any other steam-starved American rail fan would, I became quite excited recently when I found that I would be spending the month of August at Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, a town about midway on the main line of the Dominion Atlantic Railway. Immediately memories came to mind of earlier visits to that Canadian maritime province three and four years earlier when I had seen only steam locomotive power on the Dominion Atlantic. All through the Spring and early Summer months, my anticipation heightened as I heard scattered rumored reports that in Canada the situation was still little changed by the hand of progress.

Soon after crossing from Maine into the province of New Brunswick on the journey to Nova Scotia, my hopes were strengthened as we drove through the town of St. George. A rusty Canadian 4-6-0 steamer, 490, was lazily drilling a few assorted freight cars into a siding running off into the dense pine woods. Leaping from our auto for a few quick photos, I realized how extinct steam has become on the American scene. My two year old son, who delightedly shouts “choo-choo” at the first sign of a diesel in New Jersey, was frightened to tears by the black smoke, hissing steam, and pounding drivers. He quickly clambered over the seat to his mother’s arms. Little time was spent admiring this engine as it was felt that this was only a preview of greater things to come. Throughout the remaining 400 miles of the trip, only Canadian National and Canadian Pacific diesel power was seen. Arriving at Annapolis Royal, inquiries were quickly made into the Dominion Atlantic steam situation. You can imagine my disappointment when I learned that most of the passenger service on the line is handled by two RDC “Dayliners” and the vast majority of the freight is hauled by GM-EMD diesel power. In fact, apparently the only occasion on which steam locomotive power is used on the mainline is in case of emergency and I was told that no emergencies were expected in August, Swallowing my disappointment, I decided to make the most of the situation and enjoy the Dominion Atlantic as the shortline exists today.

In just three short years, the scene on the Dominion Atlantic has changed from one completely dominated by steam power to one in which only diesel power can be found regularly in use. A D.A. station-master told me in August of this year (1959) that to his knowledge there were only three steam locos left, two in storage at Kentville and possibly one ballasting between Windsor and Truro. On my first visit during the month to the Kentville headquarters of the line, I was able to find only one steamer — a 4-6-0 sleeping peacefully in the roundhouse, hardly aware of the colorful diesel switchers laboring outside. On my next visit to Kentville, I uncovered two 4-6-2 Pacifies which I had previously overlooked, numbers 2209 and 2501, stored in the shops. On this particular day, the ten-wheeler, numbered 1046 and bearing the Dominion Atlantic crest, was busily performing switching duties in the yards. The two Pacifics are lettered Canadian Pacific. Apart from these last few nearly-silent reminders, all other workhorses from the age of steam have been scrapped. (Editor’s note: Now, two and a half years later, these may be gone also).

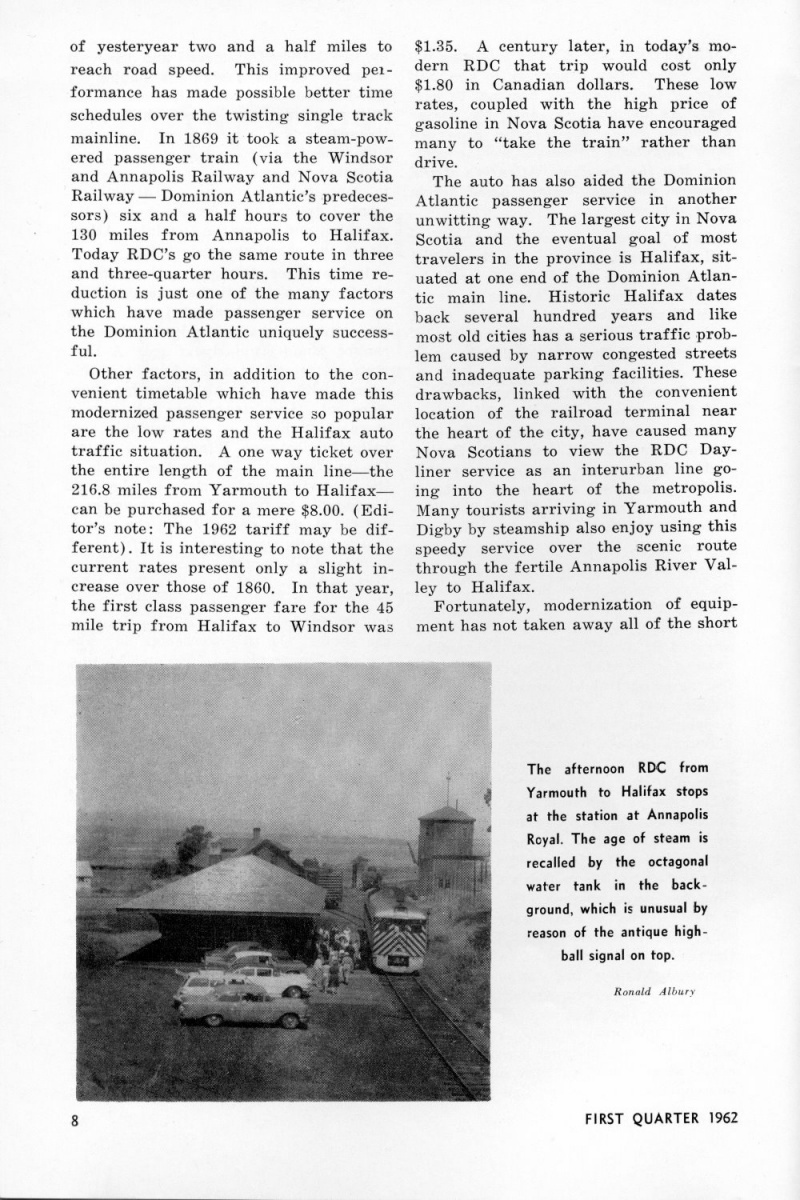

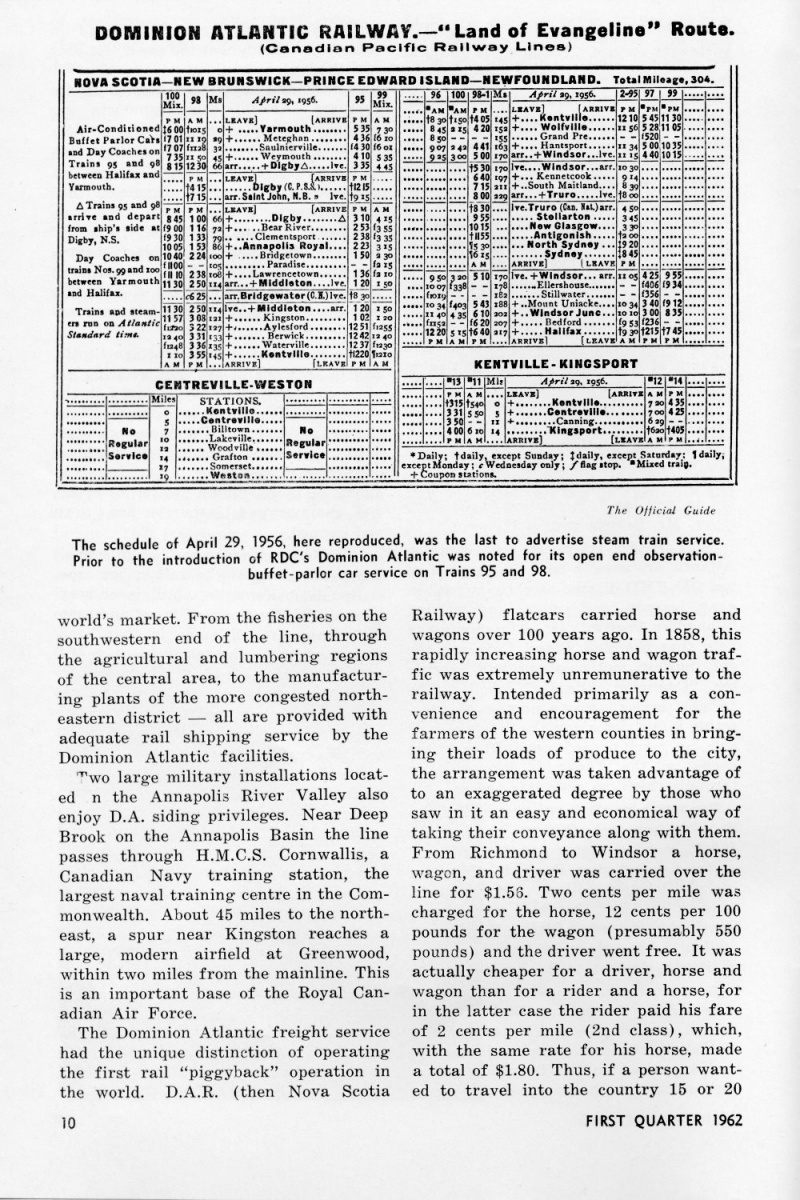

Passenger service on the Dominion Atlantic is today handled almost exclusively by the silver, maroon and yellow Rail Diesel Cars travelling singly. Occasionally, when the traffic demands it, a few elderly passenger coaches are towed over the line by a GM-EMD diesel switcher, usually associated with the more lucrative freight service. When this is necessitated, the time schedule usually suffers.

The chunky, speedy RDC’s are capable of accelerating to 50 m.p.h. in 100 yards, while it took the steam locomotive of yesteryear two and a half miles to reach road speed. This improved performance has made possible better time schedules over the twisting single track mainline. In 1869 it took a steam-powered passenger train (via the Windsor and Annapolis Railway and Nova Scotia Railway — Dominion Atlantic’s predecessors) six and a half hours to cover the 130 miles from Annapolis to Halifax. Today RDC’s go the same route in three and three-quarter hours. This time reduction is just one of the many factors which have made passenger service on the Dominion Atlantic uniquely successful.

Other factors, in addition to the convenient timetable which have made this modernized passenger service so popular are the low rates and the Halifax auto traffic situation. A one way ticket over the entire length of the main line—the 216.8 miles from Yarmouth to Halifax can be purchased for a mere $8.00. (Editor’s note: The 1962 tariff may be different). It is interesting to note that the current rates present only a slight increase over those of 1860. In that year, the first class passenger fare for the 45 mile trip from Halifax to Windsor was $1.35. A century later, in today’s modern RDC that trip would cost only $1.80 in Canadian dollars. These low rates, coupled with the high price of gasoline in Nova Scotia have encouraged many to “take the train” rather than drive.

The auto has also aided the Dominion Atlantic passenger service in another unwitting way. The largest city in Nova Scotia and the eventual goal of most travelers in the province is Halifax, situated at one end of the Dominion Atlantic main line. Historic Halifax dates back several hundred years and like most old cities has a serious traffic problem caused by narrow congested streets and inadequate parking facilities. These drawbacks, linked with the convenient location of the railroad terminal near the heart of the city, have caused many Nova Scotians to view the RDC Dayliner service as an interurban line going into the heart of the metropolis. Many tourists arriving in Yarmouth and Digby by steamship also enjoy using this speedy service over the scenic route through the fertile Annapolis River Valley to Halifax.

Fortunately, modernization of equipment has not taken away all of the short line color and atmosphere of the D.A. passenger service. The story is told that a few years ago a large group from Annapolis County drove to Halifax to attend the opening of the Provincial Parliament. During the day a heavy snowstorm made many of the highways impassable and most of the group of supporters decided to plow their way to the depot and return home via the dependable Dayliner RDC, leaving their cars in the capital city. The single car, built for 89 people, left Halifax with a reported 140 people aboard, At one way station close to Annapolis, a woman carrying a small child squeezed aboard. She glanced at a dignified looking gentleman seated near the door and said loudly, “You're that Mr. Balcom what’s a member of Parliament, ain’t you?” The dignified looking gentleman replied in the affirmative. “Well then, if you want my vote next time, you’d better hold this kid on your lap.” According to the story teller, Mr. Balcom earned the vote.

The freight trains of the Dominion _ Atlantic are usually hauled by a fleet of ten GM-EMD diesels, brightly colored in gray, maroon, and yellow, and lettered “Canadian Pacific”. (It is interesting to note that the Rail Diesel Cars are the only modern motive power still bearing the “Dominion Atlantic” label). The freight service serves a number of interesting industries along the line, and also supplies much-needed commodities to the people of the Annapolis River Valley through which the main line passes.

Beginning at the southwest end of the line in Yarmouth County, we find the D.A.R. serving that county’s $2,000,000 a year fish industry. Products of the sea include lobster, pollock, cod, haddock, “finnan haddie”, herring, and clams. Further east, from Digby, the largest scallop fishing fleet in Canada brings additional freight to be hauled by the line.

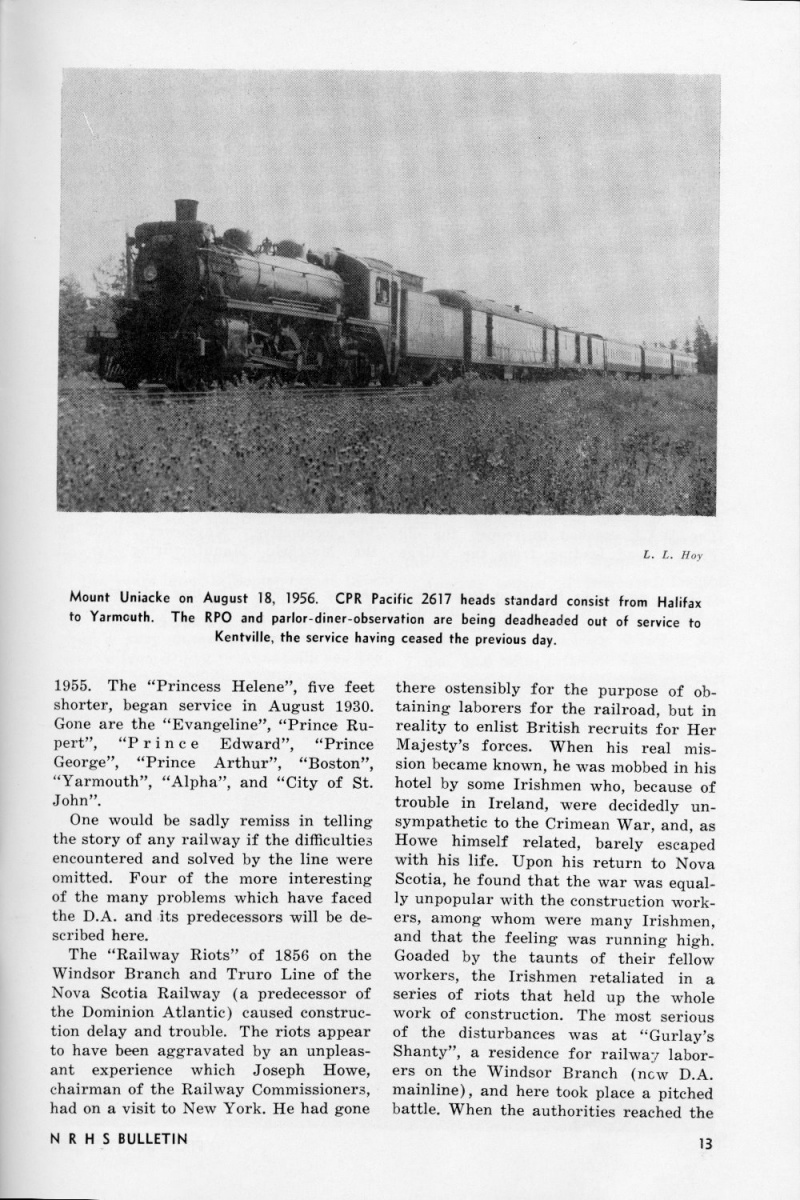

In addition to scallops, Digby County, as well as Annapolis and Kings Counties further to the east, supplies lumber to be transported on the Dominion Atlantic. Spruce, pine, hemlock, balsam, beech, birch, and maple trees are found in abundance throughout the area. Not only are they used for lumber, but also for pulpwood and many varied wood manufactures. Among these products are clothespins, crates and boxes, woodenware, staves, and, of course, railway ties.

Timber is not the only natural resource found along the Dominion line. Small deposits of high grade silica rock, diatomite, gypsum, and iron ore in the form of red hematite and black magnetite are found near D.A. trackage. Large peat bogs are worked west of Kentville and their product is shipped in box cars 7 via the Dominion Atlantic.

The most fertile area of Nova Scotia, and in fact one of the best growing regions in North America, is found in the Annapolis River Valley from Digby through Windsor. Dairying, poultry, cattle, and sheep raising, fox ranching, and fruit growing are found in abundance. Apples, plums, pears, strawberries, cherries, and blueberries are grown and canned.

Manufactures are carried on in a small degree all along the mainline, but especially about Kentville. Mill machinery, gas engines, dusting machinery, and boots and shoes, are all made in that area. Truro, which is the terminus of a 56.9 mile D.A. branch from Windsor, produces rayon, cotton and woolen wear, hats and caps, hosiery, pajamas, confectionery, builders’ supplies, creosoted poles and ties, and condensed milk and coffee.

Principal industries in Halifax, at the northeastern end of the mainline are confectionery and biscuit manufacturing, oil refining, steel shipbuilding, rope and twine manufacturing, paint and varnish making, nut and bolt founding, cloth milling, woodworking, paper box manufacturing, and spice milling. Splendid factory sites with rail privileges are available. Exceptional inducements are made by the city for the establishment of industries not competing with those existing.

And so we see that there are many varied industries whose goods and products are taken by the Dominion Atlantic on the first lap of their journey to the world’s market. From the fisheries on the southwestern end of the line, through the agricultural and lumbering regions of the central area, to the manufacturing plants of the more congested northeastern district — all are provided with adequate rail shipping service by the Dominion Atlantic facilities.

Two large military installations located n the Annapolis River Valley also enjoy D.A. siding privileges. Near Deep Brook on the Annapolis Basin the line passes through H.M.C.S. Cornwallis, a Canadian Navy training station, the largest naval training centre in the Commonwealth. About 45 miles to the northeast a spur near Kingston reaches a large, modern airfield at Greenwood, within two miles from the mainline. This is an important base of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

The Dominion Atlantic freight service had the unique distinction of operating the first rail “piggyback” operation in the world. D.A.R. (then Nova Scotia Railway) flatcars carried horse and wagons over 100 years ago. In 1858, this rapidly increasing horse and wagon traffic was extremely unremunerative to the railway. Intended primarily as a convenience and encouragement for the farmers of the western counties in bringing their loads of produce to the city, the arrangement was taken advantage of to an exaggerated degree by those who saw in it an easy and economical way of taking their conveyance along with them. From Richmond to Windsor a horse, wagon, and driver was carried over the line for $1.56. Two cents per mile was charged for the horse, 12 cents per 100 pounds for the wagon (presumably 550 pounds) and the driver went free. It was actually cheaper for a driver, horse and wagon than for a rider and a horse, for in the latter case the rider paid his fare of 2 cents per mile (2nd class), which, with the same rate for his horse, made a total of $1.80. Thus, if a person wanted to travel into the country 15 or 20 miles beyond the railway, it cost him virtually nothing to take his horse and empty wagon along with him to the point of departure.

The abuse of this system meant a loss to the railway. If, for instance, there happened to be only one person taking his conveyance, it obliged an extra platform car and a box car to be added to the train’s consist, with consequent delay in shunting and loading. The heavily loaded trains on the Windsor Branch, between Windsor and Halifax, played havoc with the roadbed, ate up fuel and tallow, and were delayed all up and down the line with this now almost unwelcome traffic. In a few years it was definitely discontinued.

And now the same idea has caught on again—in modern terms. In Canada, the C.P.R. is the leader, but the publicly-owned C.N.R. is catching up. It has ordered 400 special flatcars for delivery this fall from National Steel Car in Hamilton, Ontario, Both roads have piggyback services across Canada with service terminals at most major locations. As demand grows, they expect to open new terminals in smaller cities.

The Dominion Atlantic has always encouraged industries along its line, particularly the apple industry. Three years after the construction of the Windsor and Annapolis Railway (a D.A. predecessor) the acreage in orchards had doubled; in another three years it had tripled. The number of barrels produced has increased through the years to several million yearly — practically all handled by the D.A.R. Each year, continuing from October throughout the winter, the Dominion Atlantic apple trains rumble over the line carrying the fruit to Halifax for export overseas, or to Canadian points via the C.N.R. or C.P.R. From the 125 warehouses along the Dominion Atlantic, quantities of sometimes 35,000 barrels, loaded into specially equipped cars, are picked up from the spurs and, within the space of a few hours, delivered to the waiting liners at the Atlantic port. Delays would be costly, and there are none for the railway recognizes its responsibility in the handling of these great crops, and its well-organized and systematic service has been perfected through years of experience. The Dominion Atlantic is an integral and indispensable part of this, the valley’s greatest activity.

Not only has the line encouraged apple growing to a great degree, but also it has fostered the tourist trade, probably the second largest industry of the area which it traverses.

This part of Nova Scotia is steeped in history and local color, and the Dominion Atlantic has capitalized on this. In 1917 the railway purchased a 14 acre tract around what is believed to be the site of the ancient church from which the Acadians were deported in 1755. This deportation was forever clothed with the glamor of sentiment and romance by the poet Longfellow in his immortal work - “Evangeline”. The railway built a rustic log station and park at the spot, and it immediately became a mecca for tourists who marvelled at its beautiful gardens and reconstructed chapel and well. In 1957 the railroad deeded the area to the Federal Government and it is now a national park.

Interestingly, in later years many of the descendants of the deported Acadians have returned from the United States to Nova Scotia and have settled in the coastal area between Yarmouth and Digby, producing still another tourist attraction along the D.A. right of way. This district, known as Clare, is an excellent region for the student of folk character. The people still speak French and many of the old Acadian customs survive, even to the use of oxen a spinning wheels.

This area is interesting railroad-wise as the D.A. mainline travels a mile or so inland. The villages here are located a few hundred feet from the shore. As the tourist drives along Route 1, he notes that each little town has two signs — one sign pointing to, for example, “Saulnierville Station”, and the other to “Saulnierville Wharf”. Incidentally, this same Route 1 criss-crosses the D.A.R. line at innumerable grade crossings further east between Digby and Windsor.

Many sportsmen travel into the area yearly over the D.A. for the excellent hunting and fishing in the great forests. Other tourists are drawn to such historical attractions along the line as Fort Anne at Annapolis Royal (Canada’s oldest settlement — 1605), the Blockhouse and Sam Slick House at Windsor, and the Citadel at Halifax. Others come to search for agates and amethysts which are found close by along the Bay of Fundy shore.

The Dominion Atlantic presently has no name trains to handle these visitors. In the years before World War II the “Flying Bluenose”, sporting a red locomotive, ran during the summer months, and was the only crack train on the line. Since it is not on the timetable now, we can assume that it, like the red locomotives, was a war casualty.

The fact that Nova Scotia is a peninsula has made land travel from that province to other parts of Canada very long and inconvenient. By water, on the other hand, the distances are cut severely. For example, when we drove from Saint John, New Brunswick, to Digby, Nova Scotia, it involved 408 miles. Returning, we took the C.P.R. ferry from Digby to Saint John, a distance of 43 miles. It is small wonder, then, that the Dominion Atlantic has always been involved in steamship activity.

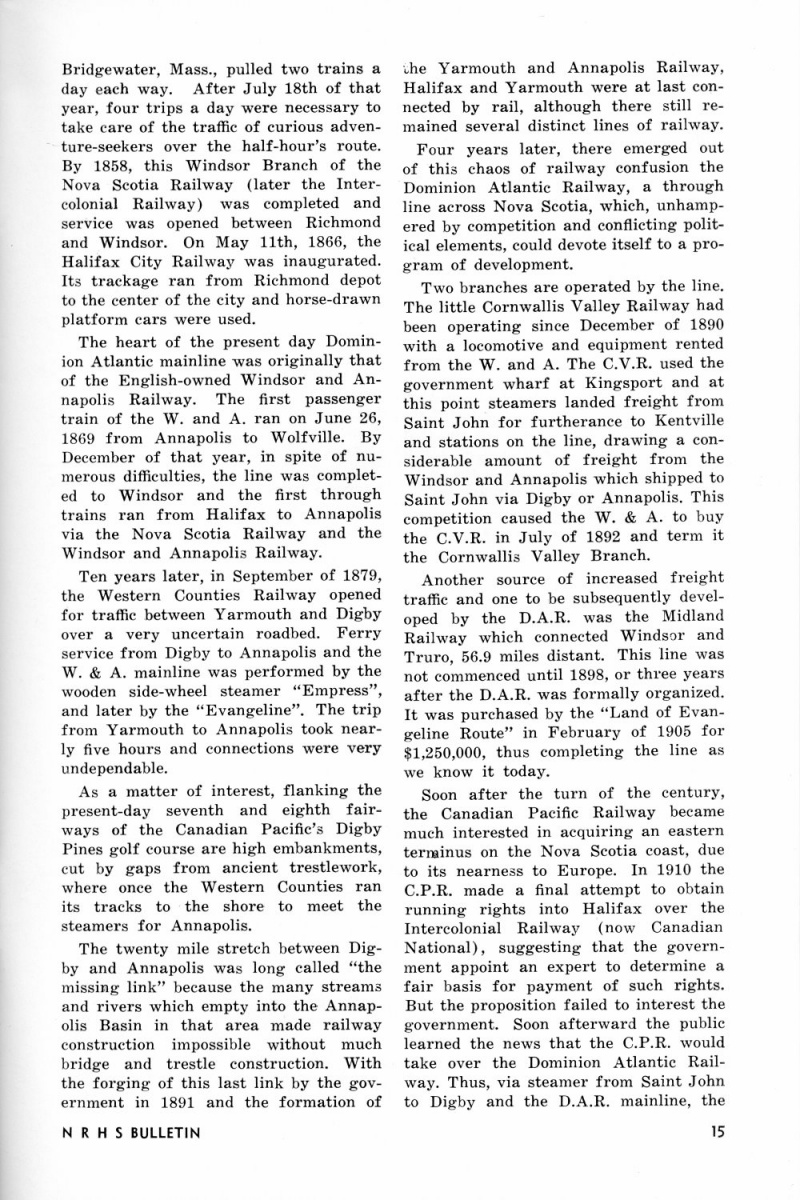

In 1901 the D.A.R. fleet consisted of nine steamships which plied between Digby - St. John, Yarmouth - Boston, and points on the Basin of Minas. Several of these vessels were even available for charter. Today, this proud fleet has shrunk to two C.P.R. ships: the M.V.“Bluenose”. between Yarmouth and Bar Harbor, Maine, and the S.S. “Princess Helene” between Digby and St. John. Both offer daily service and auto passage.

The 345-foot-long “Bluenose” was launched at Lauzon, Quebec, on May 25, 1955. The “Princess Helene”, five feet shorter, began service in August 1930. Gone are the “Evangeline”, “Prince Rupert”, “Prince Edward”, “Prince George”, “Prince Arthur”, “Boston”, “Yarmouth”, “Alpha”, and “City of St. John”.

One would be sadly remiss in telling the story of any railway if the difficulties encountered and solved by the line were omitted. Four of the more interesting of the many problems which have faced the D.A. and its predecessors will be described here.

The “Railway Riots” of 1856 on the Windsor Branch and Truro Line of the Nova Scotia Railway (a predecessor of the Dominion Atlantic) caused construction delay and trouble. The riots appear to have been aggravated by an unpleasant experience which Joseph Howe, chairman of the Railway Commissioners, had on a visit to New York. He had gone there ostensibly for the purpose of obtaining laborers for the railroad, but in reality to enlist British recruits for Her Majesty’s forces. When his real mission became known, he was mobbed in his hotel by some Irishmen who, because of trouble in Ireland, were decidedly unsympathetic to the Crimean War, and, as Howe himself related, barely escaped with his life. Upon his return to Nova Scotia, he found that the war was equally unpopular with the construction workers, among whom were many Irishmen, and that the feeling was running high. Goaded by the taunts of their fellow workers, the Irishmen retaliated in a series of riots that held up the whole work of construction. The most serious of the disturbances was at “Gurlay’s Shanty”, a residence for railway laborers on the Windsor Branch (now D.A.

mainline), and here took place a pitched battle. When the authorities reached the be the scene the rioters were arrested, the wounded removed, and with the remnants of the construction gang work was again resumed on the section.

Later, two great “acts of God” caused the young railway great difficulty. In 1869 the Saxby Gale washed out miles of the roadbed east of Wolfville. Then in in 1905, when things were just beginning to prosper for the line, snows of unprecedented proportions completely blocked the line. Traffic was suspended for weeks. Volunteers were called for and hundreds of citizens responded, among them students and professors from the Universities at Wolfville and Windsor, and for weeks they worked with pick and shovel until a passage was made for the trains. Over $100,000 had been spent by the line for snow removal alone.

A fourth, but by no means final, difficulty arose in 1917 in conjunction with the development of the Grand Pre Park. The D.A.R. wished to reopen the old French road leading from the village hill toward the Acadian chapel, and as official authority was necessary to do this, the residents of Grand Pre, willingly enough, signed the authorizing petition, Then someone conceived the notion that the railway had designs to bring the French back to Grand Pre and dispossess the English. The idea, absurd as it was, gained ground to such an extent that it thoroughly alarmed the people of the area, and the very persons who had put their names to the first petition signed a counter-petition to restrain the railway from opening the road.

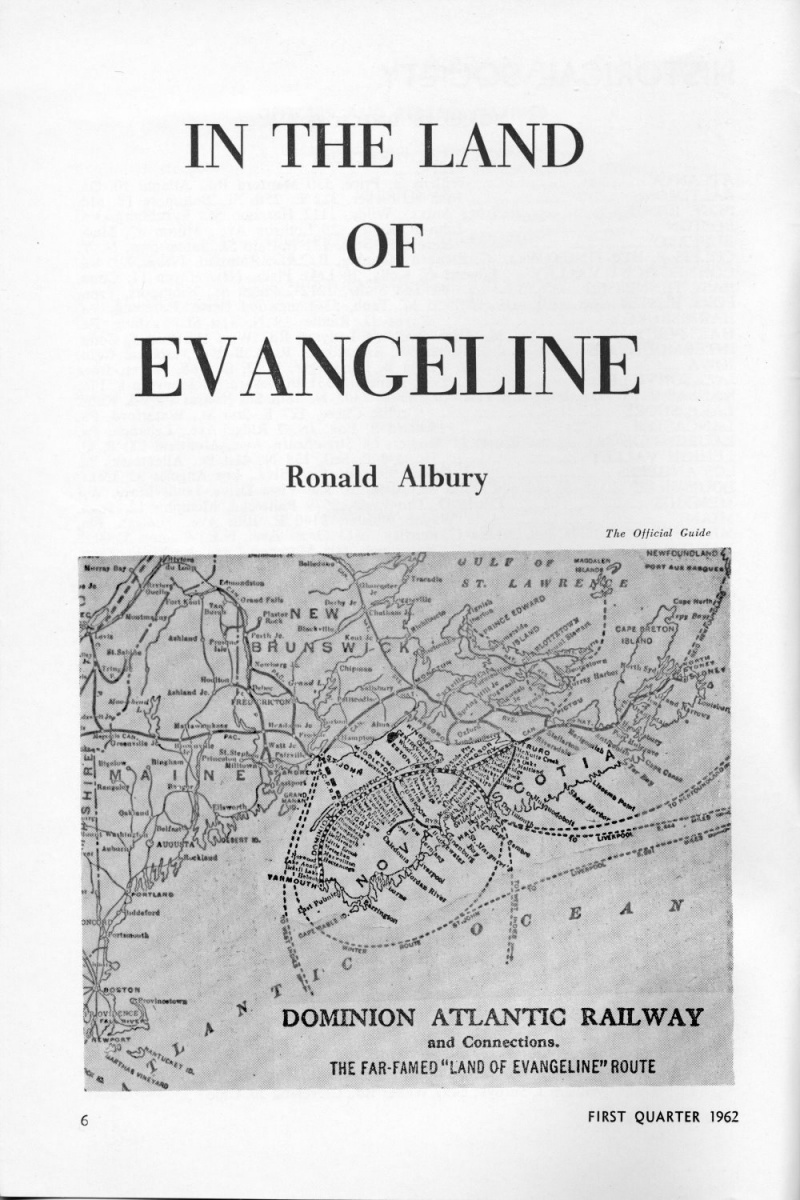

The present Dominion Atlantic Railway was formed from several distinct parts and evolved over a period of exactly fifty years — from 1855 to 1905.

On the 8th day of June, 1855, amid general rejoicing, the Nova Scotia Railway was opened to the public from Richmond, just outside of Halifax, to Sackville, a distance of just a few miles. The locomotive, “Mayflower”, built by the Mattfield Manufacturing Co. of Bridgewater, Mass., pulled two trains a day each way. After July 18th of that year, four trips a day were necessary to take care of the traffic of curious adventure-seekers over the half-hour’s route. By 1858, this Windsor Branch of the Nova Scotia Railway (later the Intercolonial Railway) was completed and service was opened between Richmond and Windsor. On May 11th, 1866, the Halifax City Railway was inaugurated. Its trackage ran from Richmond depot to the center of the city and horse-drawn platform cars were used.

The heart of the present day Dominion Atlantic mainline was originally that of the English-owned Windsor and Annapolis Railway. The first passenger train of the W. and A. ran on June 26, 1869 from Annapolis to Wolfville. By December of that year, in spite of numerous difficulties, the line was completed to Windsor and the first through trains ran from Halifax to Annapolis via the Nova Scotia Railway and the Windsor and Annapolis Railway.

Ten years later, in September of 1879, the Western Counties Railway opened for traffic between Yarmouth and Digby over a very uncertain roadbed. Ferry service from Digby to Annapolis and the W. & A. mainline was performed by the wooden side-wheel steamer “Empress”, and later by the “Evangeline”, The trip from Yarmouth to Annapolis took nearly five hours and connections were very undependable.

As a matter of interest, flanking the present-day seventh and eighth fairways of the Canadian Pacific’s Digby Pines golf course are high embankments, cut by gaps from ancient trestlework, where once the Western Counties ran its tracks to the shore to meet the steamers for Annapolis.

The twenty mile stretch between Digby and Annapolis was long called “the missing link” because the many streams and rivers which empty into the Annapolis Basin in that area made railway construction impossible without much bridge and trestle construction. With the forging of this last link by the government in 1891 and the formation of the Yarmouth and Annapolis Railway, Halifax and Yarmouth were at last connected by rail, although there still remained several distinct lines of railway.

Four years later, there emerged out of this chaos of railway confusion the Dominion Atlantic Railway, a through line across Nova Scotia, which, unhampered by competition and conflicting political elements, could devote itself to a program of development.

Two branches are operated by the line. The little Cornwallis Valley Railway had been operating since December of 1890 with a locomotive and equipment rented from the W. and A. The C.V.R. used the government wharf at Kingsport and at this point steamers landed freight from Saint John for furtherance to Kentville and stations on the line, drawing a considerable amount of freight from the Windsor and Annapolis which shipped to Saint John via Digby or Annapolis, This competition caused the W. & A. to buy the C.V.R. in July of 1892 and term it the Cornwallis Valley Branch.

Another source of increased freight traffic and one to be subsequently developed by the D.A.R. was the Midland Railway which connected Windsor and Truro, 56.9 miles distant. This line was not commenced until 1898, or three years after the D.A.R. was formally organized. It was purchased by the “Land of Evangeline Route” in February of 1905 for $1,250,000, thus completing the line as we know it today.

Soon after the turn of the century, the Canadian Pacific Railway became much interested in acquiring an eastern terminus on the Nova Scotia coast, due to its nearness to Europe. In 1910 the C.P.R. made a final attempt to obtain running rights into Halifax over the Intercolonial Railway (now Canadian National), suggesting that the government appoint an expert to determine a fair basis for payment of such rights. But the proposition failed to interest the government. Soon afterward the public learned the news that the C.P.R. would take over the Dominion Atlantic Railway. Thus, via steamer from Saint John to Digby and the D.A.R. mainline, the Canadian Pacific was enabled to reach the port of Halifax. On January 1, 1912, the 999-year lease began and the D.A.R. became part of the world’s greatest travel dydtem.

As a subsidiary of the Canadian Pacific, the Dominion Atlantic Railway has not only fulfilled its obligations as a public carrier, reviving and stimulating progress along its line from Yarmouth to Halifax, and its Midland and Cornwallis Valley branches, but it has initiated and carried out improvements that have revolutionized the whole economic outlook of the province. To Nova Scotians the “Dominion Atlantic” is a symbol of unification and progress and they jealously guard its identity. Most folks who live along the line will tell you that “it’s a mighty good railway”, this line " which ranks among the best of the shortline carriers in North America.

The Dominion Atlantic’s engine roster, as of August 1959, included three steam locomotives: Ten-wheeler 1046 (lettered Dominion Atlantic) and Pacifics 2209 and 2501 (both lettered Canadian Pacific). Also lettered for the parent road are ten EMD units, 8131-8140. The two RDC’s, 9058-9059, bear the Dominion Atlantic name on their letterboard.

By contrast, here is a summary of the Windsor and Annapolis roster as of 1869:

Six “large” engines (wheel arrangement unknown to the writer), named Evangeline, Gabriel, Gaspareau, Grand Pre, Hiawatha, and Minnehaha. These were all purchased new and built by Fox, Walker and Company. Weight, 50 tons.

One “medium” engine, Portland-built, named St. Lawrence.

Two second-hand “small” engines, Joseph Howe and Sir Gaspard le Merchant. Both were purchased second-hand from the government for $7,000.

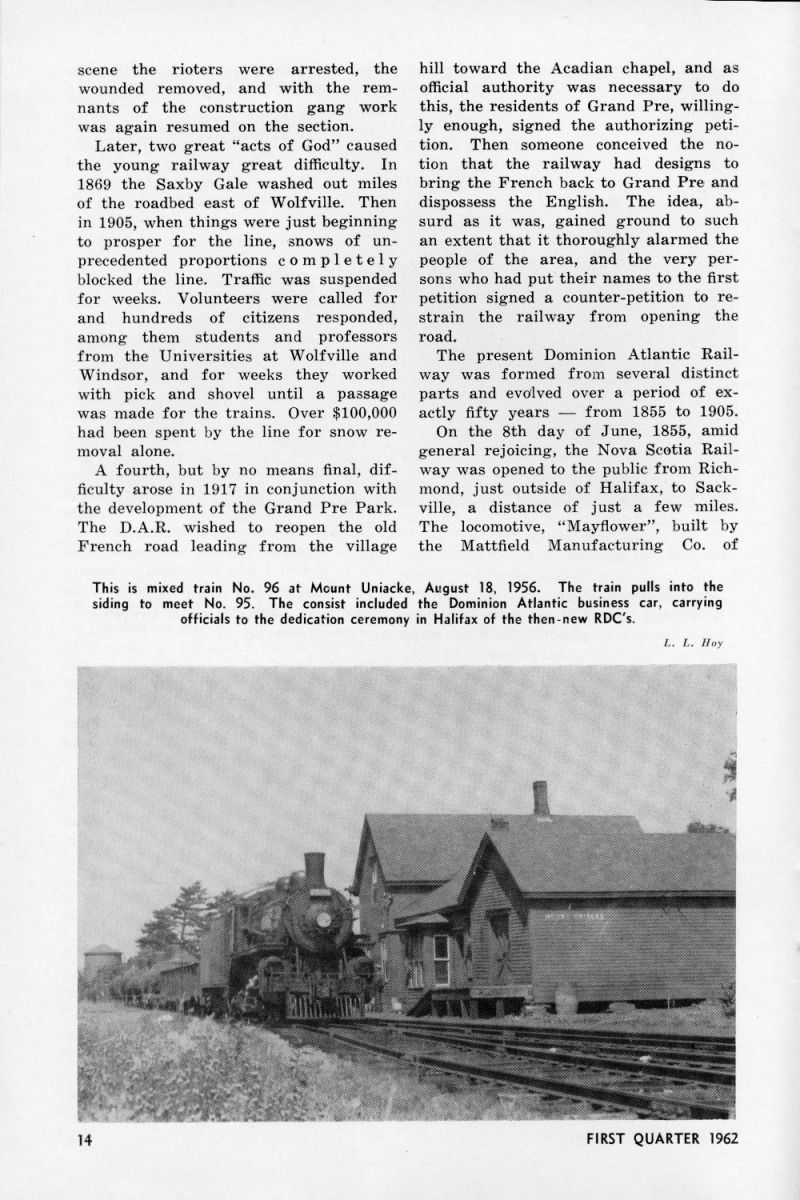

The road also owned six first-class cars and six second-class cars, all built at Saint John. Freight equipment consisted of 20 covered goods cars, 20 cattle and horse cars, 80 platform cars, 12 trolleys, and 2 snow plows. Freight equipment was built at Portland, Kentville, Windsor, and Wolfville. Engine sheds were located at Kentville and Annapolis, each housing three locomotives.